Jan Albers: The Energetic Grid

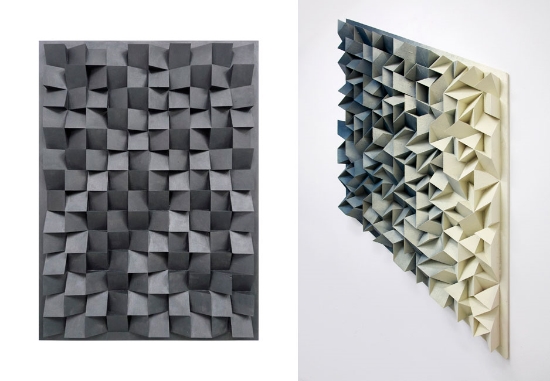

Maybe it was the garden-like quality of Jan Albers work that first attracted Sean to it. In his recent Henry Hurt vs. Holly Heal series (seen below) the skewed squares seem to have the character of a flower, like gridded petals blowing in the wind.

The pieces in the series have a dimensionality that expands as the as the viewing angle changes. As constructions, they're ingeniously engineered. Their texture radiates a kind of kinetic energy, seeming to move before your eyes. Their structure is both flower-like and architectural, like something made by bees in a kaleidoscope. The references to Cubism are hard to deny. The pieces are built from polystyrene (the stuff packing peanuts are made from) and/or wood and then covered in spray paint, or as in the gray piece above, graphite.

The sum of artist Jan Albers's googleable biography is pretty much this: Born in Wuppertal Germany in 1971. Grew up in Namibia. Presently lives and works in Düsseldorf. Perhaps what's more interesting is his extensive CV which includes awards and an impressively copious list of exhibitions that go around the world (including shows in Los Angeles). He's creative fascinations center on the idea of creation and destruction, health and injury––especially that of the flesh––and myriad of other yin-yang binaries (though bent decidedly more toward the yin). A fact that may be reflected in his color palette which tends toward the industrial.

Search google for glimpses of his work and you'll find it intermixed with that of his more famous predecessor and fellow countryman Josef Albers (no relation). While both artists share a preoccupation with the square, unlike the deliberate painterly flatness of Josef's work (he being known for Homage to the Square), Jan's experiments feature layers and dimensions of both form and subtext.

By his own admission, Albers operates under the attitude that "painting is dead." His work seeks to push beyond painting into new territorial hybrids. Emblematic of this ambition is his work with the grid in which he attempts to work within it and break out of it at the same time. Right angles and squares abound even as he skews them and breaks them down. As in traditional painting, Albers employs light, shadow, depth, and volume––albeit quite literally. The format and scale is very much within the painting tradition, though his surfaces are painted out of a spray can rather than with a brush. In the pieces immediately below the material is again polystyrene; next below the work includes ceramic.

Unlike the more formal grids of Agnes Martin, Albers wrestles with his grid. For him the grid is only a starting point and the work revels in its decay––a foundation to stage the chaos on. Albers makes it a point to feature close-up photographs of bruised arms and fingers alongside his work, making the comparison of his surfaces with that of tortured and injured flesh.

According to a review in the LA Times, "It's this tension between geometric rigor and the messy efflorescence of injury and healing that compels."

One could argue that the pieces don't require a backstory at all. They stand alone well enough on their own.