Rirkrit Tiravanija and the Politics of Cooking

Interview by William Hanley

Rirkrit Tiravanija bends over his potter’s wheel with the concentration of an ambitous amatuer. As he carefully forms a spinning wad of clay into a bowl, he seems oblivious to the visitors who have just arrived at Greenwich House Pottery in New York City, where he finished a two-month residency in November. His French bulldog, Harry, eyes the guests briefly before going back to snoozing on the floor next to the wheel. When he’s finished, Tiravanija holds up his latest ceramic creation, one of a few hundred bowls he’s crafted since he began working with clay, earlier this year. Taking a break to talk about the work, he has an assured nonchalance, like someone with a generally strong sense of purpose and direction but no particular place to be right now. “It’s kind of like a meditative activity,” he says of making pottery, though he’s not one to clear his head. “It gives you time to think about everything else you have to do, or could be doing, or dealing with. It’s like cooking that way.”

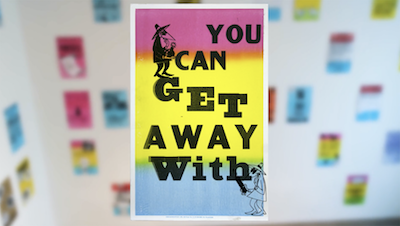

Tiravanija knows a thing or two about cooking. He rose to prominence as one of a group of artists working within a strain of participatory art now often gathered under the broad umbrella of social practice. At its core, Tiravanija’s work tees up situations that invite participants to interact with one another. This has taken the shape of everything from a 2002 re-creation of his New York apartment at the 2002 Biennial in Liverpool to a pirate television station broadcasting from the Guggenheim Museum in 2005. But Tiravanija is best known for cooking and serving meals in spaces typically reserved for more traditional exhibitions.

Some of the pottery Tiravanija produced was shipped to Frankfurt in October, where he and Tobias Rehberger sold them, along with a varying menu of dishes, at a temporary stall in the city’s historic market. Other pieces may travel to Singapore, Tiravanija says, to be used in a temporary tea house he is building at the National Gallery for a January exhibition there. His ceramics residency coincided with an exhibition at his friend and longtime dealer Gavin Brown’s galleries in New York. It featured his archive of Super 8 films, studies of people he has observed over decades, as well as screenings of his remake of Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s 1974 film “Ali: Fear Eats the Soul.” Wearing a clay-spattered apron, with Harry dutifully dozing in his lap, Tiravanija spoke about how he started cooking and why gathering people for a meal can be a defiant act.

It’s novel to see you sitting at the wheel rather than standing over the stove. Why did you start making ceramics?

Well, I’ve been making tea rooms here and there, and I was interested in the medicinal side of coffee and tea, so looking at how to serve it seemed natural. At the same time, it’s kind of interesting because I teach, and I’ve noticed the kiln in the department has become very active in the last three years. I think it has to do with people discovering the material and a getting-back-to-the-earth kind of thing. If we weren’t in the city, you could take the clay out of the ground and make everything literally from scratch. And it can also go the other way: You can use the object and return it to the ground. One of the things I’m interested in doing in the future is to make a project where you use the object and then you kind of return it—after you drink the tea, then you smash the cups.

View article

Read More